OsteoPur, We are living in the age of the replacement. A hip wears out? We swap in titanium. A tooth decays? We crown it with porcelain. A blood vessel clogs? We stent it with stainless steel. For decades, the paradigm of medical intervention has been fundamentally inert. We patch the body with materials that are foreign, static, and lifeless. They are brilliant, life-extending solutions, but they are also permanent admissions of defeat: the body part is gone, and all we can offer is a sophisticated, biological stand-in.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!But what if the paradigm could shift from replacement to regeneration?

What if, instead of a titanium rod, we could implant a living scaffold that guides your own body to rebuild its own bone, perfectly, completely, and permanently? This is not science fiction. This is the frontier being defined by a groundbreaking technological platform known as OsteoPur.

The name itself is a elegant portmanteau: Osteo, from the Greek for bone, and Pur, from the Latin for pure, but also hinting at its function as a porous, purifying scaffold. At its core, OsteoPur is a class of biomaterial, but to call it that is like calling the internet a series of tubes. It is a bioactive, architecturally intelligent matrix designed to harness and amplify the body’s innate healing power. It is a technology that doesn’t just fix us; it talks to our cells, instructing them to rebuild what was lost.

This is the story of OsteoPur—a deep dive into its molecular genius, its vast potential to rewrite medical textbooks, and the profound philosophical implications of a future where our bodies can truly heal themselves.

Part 1: The Problem with Permanence – Why Inert Implants Fail Us

To understand the revolution of OsteoPur, we must first appreciate the limitations of the materials we currently trust with our lives.

The Foreign Body Problem:

The human immune system is a masterpiece of defensive paranoia. Its primary directive is simple: “If it’s not ‘self,’ attack it.” A titanium screw, a polyethylene joint, a stainless-steel plate—all are recognized as foreign. While we’ve engineered these materials to be as bio-inert as possible, the body never truly accepts them. It walls them off in a process called fibrotic encapsulation, creating a layer of scar tissue that isolates the invader. This can lead to chronic, low-grade inflammation, reduced functionality, and in some cases, eventual implant rejection or failure.

The Issue of Mechanical Mismatch:

Bone is not a static, rigid bar. It is a dynamic, living composite material—a perfect blend of strong but brittle hydroxyapatite (the mineral) and flexible collagen (the protein). This gives it a unique combination of strength and resilience, a specific “Young’s Modulus.” Titanium, while strong, has a much higher modulus. This creates a problem known as “stress shielding.” The rigid metal implant bears the majority of the mechanical load, which sounds good, but it inadvertently shields the surrounding bone from the natural stresses it needs to stay healthy. Sensing it is no longer needed, the body begins to resorb the bone, leading to weakening and loosening of the very implant that was meant to save it.

The Finality of Failure:

Perhaps the greatest limitation of inert implants is their biological dead-end nature. They do not grow, they do not heal, and they do not integrate. If a synthetic bone graft fails to fuse, it remains a dead, obstructive block in the body. There is no second chance, no cellular negotiation. It is a static solution in a dynamic biological environment, and over a patient’s lifetime, this fundamental incompatibility often reveals itself.

OsteoPur emerges not as an incremental improvement, but as a categorical rejection of this inert paradigm. It asks a radical question: What if the implant wasn’t a foreign object, but a temporary guide?

Part 2: The OsteoPur Blueprint – Architecture as Instruction

OsteoPur is not a single chemical formula, but a platform technology defined by a set of core design principles. Its genius lies in how it mimics the body’s own native environment so perfectly that cells are fooled into treating it as a natural part of themselves.

1. The Material: A Familiar Language

While specific formulations are proprietary, OsteoPur materials are typically based on bioceramics like calcium phosphates (e.g., hydroxyapatite) or certain bio-polymers. The key is that these materials are bioactive. They are chemically similar to the mineral component of our own bones. When placed in the body, they do not provoke a defensive scar-tissue response. Instead, they engage in a controlled, slow dissolution, releasing benign ions (calcium and phosphate) into the local environment. This does two things: it provides the raw building blocks for new bone, and it sends a powerful chemical signal to the body’s master cells that says, “Bone-building site: assemble here.”

2. The Micro-Architecture: A City for Cells

This is where the “Pur” (porous) aspect becomes revolutionary. Under an electron microscope, OsteoPur reveals a labyrinthine, interconnected network of pores. This is not random; it is meticulously engineered.

-

Macropores (100-500 microns): These are the wide boulevards, large enough for cells to migrate into, for blood vessels to sprout (a process called angiogenesis), and for new bone tissue to form. Without these large pores, the interior of the scaffold would be a barren, inaccessible wasteland.

-

Micropores (1-10 microns): These are the side streets and alleys. They dramatically increase the surface area available for protein adsorption and cell attachment. They also facilitate the capillary action of bodily fluids, wicking nutrients deep into the scaffold and keeping the nascent tissue hydrated.

This hierarchical pore structure is a direct mimic of natural bone trabeculae. It isn’t just a structure; it’s a pre-built, fully serviced development site, ready for cellular tenants to move in and start construction.

3. The Surface Topography: The Nano-Scale Welcome Mat

At the nanoscale, the surface of OsteoPur is anything but smooth. It is textured, pitted, and rough—a landscape that osteoblasts (bone-building cells) instinctively recognize and cling to. This nanotexture triggers specific genetic programs within the cells, encouraging them to proliferate, mature, and begin secreting new bone matrix. The material, through its physical shape alone, is issuing commands at a molecular level.

In essence, an OsteoPur implant is a three-dimensional, bioactive, and architecturally perfect instruction manual. It says: “Migrate here. Lay down new bone here. Connect blood vessels here. When you are done, I will gracefully disappear.”

Part 3. From Theory to Trauma: The Real-World Applications of OsteoPur

The potential of OsteoPur stretches across virtually every medical discipline that deals with structural repair. It is moving from laboratory benchtops to operating rooms, with transformative results.

Application 1: The Critical-Sized Defeat – Beyond the Gold Standard

In complex trauma, cancer resections, or severe congenital defects, surgeons often face “critical-sized defects”—gaps in bone so large that the body cannot bridge them on its own. The current gold standard is an autograft: harvesting bone from the patient’s own hip or femur. This is effective, but it comes at a terrible cost: a second, often painful surgical site, limited supply, and potential complications at the donor site.

OsteoPur is poised to make autografts obsolete. Surgeons can now pack a custom-shaped OsteoPur scaffold into the defect. Almost immediately, the scaffold acts as a magnet for the patient’s own stem cells and growth factors from the surrounding bone marrow and blood. The body doesn’t see it as an implant; it sees it as a damaged bone framework that needs repairing. Over 12-24 months, the scaffold is progressively resorbed as the patient’s own, fully vascularized, living bone replaces it. The result is not a fusion, but a true regeneration. The body has healed what was once considered unhealable.

Case Study: The Jawbone Reborn

Consider a patient with a severe jawbone infection (osteomyelitis) requiring a massive resection. Traditionally, reconstruction would be a multi-stage, years-long ordeal involving metal plates and multiple graft harvests. With OsteoPur, a CT scan is used to 3D-print a patient-specific jawbone scaffold. During a single surgery, this scaffold is implanted. Post-operative scans over the next two years would show a breathtaking transformation: the white, radio-dense scaffold slowly fading, while the slightly less-dense, but unmistakable, pattern of new living bone takes its place, complete with a new mandibular canal for the nerve to run through. The patient doesn’t just get a repair; they get their face back.

Application 2: Spinal Fusion – Fusing with Finesse

Spinal fusion surgery, which permanently connects two or more vertebrae, relies on creating a solid bridge of bone. Currently, this is achieved with metal cages packed with bone graft material. The metal cage provides immediate stability, but the long-term success depends on the bone growing through and around it.

OsteoPur cages are now being developed. These cages provide the initial structural support, but their OsteoPur core actively orchestrates the fusion process from the inside out. Because it encourages such rapid and robust bone growth, the fusion is stronger and occurs faster. Furthermore, once the fusion is complete, the OsteoPur cage is largely resorbed, leaving a fully natural bone bridge without a permanent metal artifact. This eliminates long-term risks like metal sensitivity, corrosion, and stress-shielding on the adjacent vertebrae.

Application 3: Dental and Craniofacial Regeneration

In dentistry, OsteoPur is revolutionizing procedures like socket preservation after a tooth extraction and sinus lifts before dental implant placement. Instead of watching the jawbone shrink away after an extraction, dentists can fill the socket with OsteoPur granules. The scaffold preserves the volume and architecture of the site, creating a perfect foundation for a future implant and eliminating the need for later, more complex bone grafting. For children with craniofacial birth defects, OsteoPur offers the hope of surgeries that grow with the child, as the regenerated bone remains living and dynamic, not a static, obstructive plate.

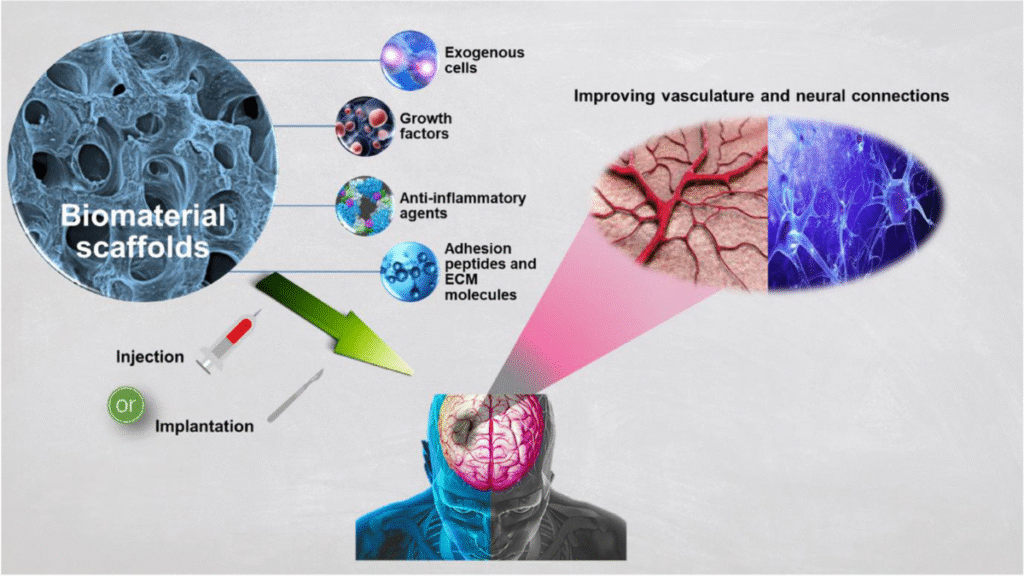

Application 4: The Future Frontier – Drug Delivery and Beyond

The OsteoPur scaffold is also a perfect delivery vehicle. Its vast surface area and porous network can be impregnated with growth factors (like BMPs), antibiotics, or even stem cells. Imagine an OsteoPur scaffold for a soldier with a bomb-blast injury: it could be loaded with antibiotics to prevent infection, growth factors to accelerate vascularization, and stem cells to supercharge the regeneration process. The scaffold becomes a programmable, targeted therapeutic system, releasing its payload in a controlled manner exactly where and when it is needed.

Part 4: The Hurdles on the Path to Prometheus

The promise of OsteoPur is immense, but its path to widespread clinical use is paved with significant scientific, regulatory, and economic challenges.

The Engineering Trilemma: Strength vs. Porosity vs. Resorption Rate

Designing an OsteoPur scaffold is a constant balancing act. You need it to be:

-

Strong enough to withstand physiological loads immediately after implantation.

-

Porous enough to allow for full cellular infiltration and vascularization.

-

Resorbable at the right rate—slowly enough to provide support during healing, but quickly enough to get out of the way once its job is done.

A scaffold that is too strong is often too dense, with inadequate porosity. A scaffold that resorbs too quickly can collapse before the new bone is mature. Achieving this perfect harmony for every single clinical indication is the central engineering challenge.

The Regulatory Labyrinth:

OsteoPur products are classified as Class III medical devices by agencies like the FDA—the most stringent category. They are not just devices; they are “combination products” that behave like drugs and tissues. Proving their safety and efficacy requires massive, long-term, and astronomically expensive clinical trials. Regulators need to be convinced not just that the scaffold is safe, but that the new bone it stimulates is functionally equivalent to native bone over the course of a patient’s entire life.

The Cost of Creation:

The processes involved—from the synthesis of high-purity bioceramics to the precision of 3D printing at the micron scale—are currently expensive. For OsteoPur to achieve its democratizing potential, manufacturing processes must be scaled and refined to bring costs down, ensuring it’s not a technology only for the wealthy.

The Surgeon as Orchestrator:

This technology also demands a shift in surgical skill. Implanting an OsteoPur scaffold is different from placing a screw. The surgeon must understand the biology, handle the material with care (as it can be brittle), and create a healthy biological bed (good blood supply, viable tissue) for the scaffold to work its magic. It transforms the surgeon from a mechanic into a conductor of a biological orchestra.

Part 5: The Philosophical Horizon – What Does It Mean to “Heal”?

Beyond the operating room, the success of OsteoPur forces us to confront deeper questions about the nature of healing and the future of the human body.

The End of the “Bionic” Era?

The 20th century was the age of the bionic man—the dream of replacing our frail biology with superior machinery. OsteoPur points in a different direction: the age of regenerative biology. The goal is no longer to become more machine-like, but to become more perfectly, resiliently biological. It suggests that the ultimate technology is not titanium, but our own innate, if often dormant, capacity for self-renewal.

The Redefinition of Chronicity:

Conditions like severe osteoarthritis or degenerative disc disease are currently managed as chronic, progressive ailments. We treat symptoms and delay the inevitable. OsteoPur and its descendants offer the possibility of moving from management to resolution. Could we one day not just replace a worn-out hip, but regenerate the cartilage within it? This would redefine what it means to live with a chronic musculoskeletal condition.

The Specter of Enhancement:

If we can perfectly regenerate a fractured bone, what about strengthening a healthy one? The line between therapy and enhancement is notoriously blurry. Could OsteoPur-derived technologies be used by athletes to create stronger skeletons? Or by astronauts to combat bone loss in zero-gravity? The ethical framework for such applications is yet to be built.

Conclusion: The Scaffold Within and Without

OsteoPur is more than a medical device. It is a symbol of a fundamental shift in our relationship with technology and our own bodies. For centuries, our tools have been external, separate from us. We used a hammer, we drove a car, we installed a pacemaker. OsteoPur represents a new class of technology that is temporary, integrative, and instructional. It is a technology that becomes a part of us, not to stay, but to teach, to guide, and then to vanish, leaving us whole.

It is a humble technology, one that acknowledges the body’s wisdom rather than seeking to override it. It provides the scaffold and the blueprint, but it lets the body—the ultimate craftsman—do the work.

The promise of OsteoPur is a future where a devastating injury or a degenerative disease is not a life sentence of metal and plastic, but a temporary setback. It is a future where the MRI scan after a major surgery shows not the stark, alien whiteness of a metal implant, but the gentle, familiar grey of living, regenerated bone. It is the promise of healing that is not just about restoring function, but about restoring self. In the intricate, porous lattice of OsteoPur, we are building the foundation for that future, one cell at a time.